The National Science Foundation's blog, Discovery. July 14, 2017

by Stanley Dambroski and Madeline Beal

From an outside perspective, understanding a spoken language versus a signed language seems like it might involve entirely different brain processes. One process involves your ears and the other your eyes, and scientists have long known that different parts of the brain process these different sensory inputs.

From an outside perspective, understanding a spoken language versus a signed language seems like it might involve entirely different brain processes. One process involves your ears and the other your eyes, and scientists have long known that different parts of the brain process these different sensory inputs.

To scientists at the University of Chicago interested in the role rhythm plays in how humans understand language, the differences between these inputs provided an opportunity for experimentation. The resulting study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences helps explain that rhythm is important for processing language whether spoken or signed.

Previous studies have shown the rhythm of speech changes the rhythm of neural activity involved in understanding spoken language. When humans listen to spoken language, the brain's auditory cortex activity adjusts to follow the rhythms of sentences. This phenomenon is known as entrainment.

But even after researchers identified entrainment, understanding the role of rhythm in language comprehension remained difficult. Neural activity changes when a person is listening to spoken language -- but the brain also locks onto random, meaningless bursts of sound in a very similar way and at a similar frequency.

That's where the University of Chicago team saw an experimental opportunity involving sign language. While the natural rhythms in spoken language are similar to what might be considered the preferred frequency for the auditory cortex, this is not true for sign language and the visual cortex. The rhythms from the hand movements in ASL are substantially slower than that of spoken language.

The researchers used electroencephalography (EEG) to record the brain activity of participants as they watched videos of stories told in American Sign Language (ASL). One group was made up of participants who were fluent in ASL, while the other was made up of non-signers. The researchers then analyzed the rhythms of activity in different regions of the participants' brains.

The brain activity rhythms in the visual cortex followed the rhythms of sign language. Importantly, the researchers observed entrainment at the low frequencies that carry meaningful information in sign language, not at the high frequencies usually seen in visual activity.

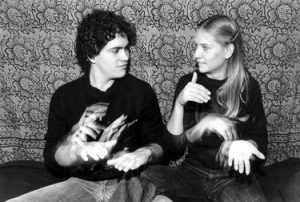

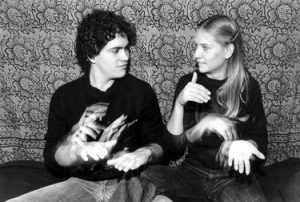

Daniel Casasanto

"By looking at sign, we've learned something about how the brain processes language more generally," said principal investigator Daniel Casasanto, Professor of Psychology at the University of Chicago (now Professor of Human Development at Cornell University). "We've solved a mystery we couldn't crack by studying speech alone."

While the ASL-fluent and non-signer groups demonstrated entrainment, it was stronger in the frontal cortex for ASL-fluent participants, compared to non-signers. The frontal cortex is the area of the brain that controls cognitive skills. The authors postulate that frontal entrainment may be stronger in the fluent signers because they are more able to predict the movements involved and therefore more able to predict and entrain to the rhythms they see.

"This study highlights the importance of rhythm to processing language, even when it is visual. Studies like this are core to the National Science Foundation's Understanding the Brain Initiative, which seeks to understand the brain in action and in context," said Betty Tuller, a program manager for NSF's Perception, Action, and Cognition Program. "Knowledge of the fundamentals of how the brain processes language has the potential to improve how we educate children, treat language disorders, train military personnel, and may have implications for the study of learning and memory."

Daniel Casasanto, a new member of the HD faculty, heads an NSF investigation of brain areas activated by hand movements when communicating through ASL.

Daniel Casasanto, a new member of the HD faculty, heads an NSF investigation of brain areas activated by hand movements when communicating through ASL. In a new study led by Anthony Ong, people who experienced the widest range of positive emotions had the lowest levels of inflammation throughout their bodies.

In a new study led by Anthony Ong, people who experienced the widest range of positive emotions had the lowest levels of inflammation throughout their bodies. arianella Casasola is working with Head Start Centers and day schools in New York City to promote development of spatial skills and language acquisition in preschoolers.

arianella Casasola is working with Head Start Centers and day schools in New York City to promote development of spatial skills and language acquisition in preschoolers. New research by Adam Anderson reveals why the eyes offer a window into the soul.

New research by Adam Anderson reveals why the eyes offer a window into the soul. Students in Valerie Reyna's Laboratory for Rational Decision Making welcome the Ithaca Youth Bureau's College Discovery Program for workshops on neuroscience and concussion risks.

Students in Valerie Reyna's Laboratory for Rational Decision Making welcome the Ithaca Youth Bureau's College Discovery Program for workshops on neuroscience and concussion risks. Daniel Rosenfeld '18 and his adviser Anthony Burrow, have developed a new way of thinking about what it is to be a vegetarian.

Daniel Rosenfeld '18 and his adviser Anthony Burrow, have developed a new way of thinking about what it is to be a vegetarian.

NPR's Science Friday discusses risky decisions and the teenage brain

NPR's Science Friday discusses risky decisions and the teenage brain

From an outside perspective, understanding a spoken language versus a signed language seems like it might involve entirely different brain processes. One process involves your ears and the other your eyes, and scientists have long known that different parts of the brain process these different sensory inputs.

From an outside perspective, understanding a spoken language versus a signed language seems like it might involve entirely different brain processes. One process involves your ears and the other your eyes, and scientists have long known that different parts of the brain process these different sensory inputs.