By Karene Booker

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, March 5, 2013

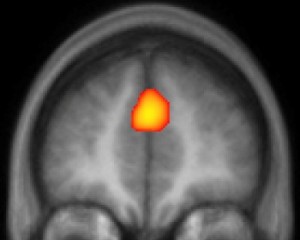

Region of the brain in medial prefrontal cortex where patterns of activity can be decoded to determine who someone is thinking about. Image provided by Nathan Spreng

Our mental picture of another person produces unique patterns of brain activation that can be detected using advanced imaging techniques, report Cornell neuroscientist Nathan Spreng and his colleagues in a study published online in Cerebral Cortex.

"When we looked at our data, we were shocked that we could successfully decode who our participants were thinking about based on their brain activity," said Spreng, the study's lead author, with Demis Hassabis of University College London, and an assistant professor of human development and the Rebecca Q. and James C. Morgan Sesquicentennial Faculty Fellow in Cornell's College of Human Ecology.

"Our findings shed light on how the brain formulates models of people's personality in order to anticipate their behavior -- a faculty critical for success in the social world," Spreng added.

For their study, the researchers asked 19 young adults to learn about the personalities of four people who differed on key personality traits. Participants were given different scenarios (i.e., sitting on a bus when an elderly person gets on, and there are no seats) and asked to imagine how a specified person would respond. During the task, their brains were scanned using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow.

The researchers found that different patterns of brain activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) were associated with each of the four different personalities. In other words, which person was being imagined could be accurately identified based solely on the brain activation pattern.

The results suggest that the brain codes the personality traits of others in distinct brain regions, and that this information is integrated in the mPFC to produce an overall personality model used to plan social interactions, the authors said.

"Prior research has implicated the anterior mPFC in social cognition disorders such as autism, and our results suggest people with such disorders may have an inability to build accurate personality models," said Spreng. "If further research bears this out, we may ultimately be able to identify specific brain activation biomarkers not only for diagnosing such diseases, but for monitoring the effects of interventions."

The study, published online in Cerebral Cortex, was also co-authored by Andrie Rusu, Vrije Univesiteit; Raymond Mar, York University; and Clifford Robbin and Daniel L. Schacter, Harvard University.

The research was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust and the National Institutes of Health.

Karene Booker is an extension support specialist in the Department of Human Development.