By Ted Boscia

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, March 20, 2014

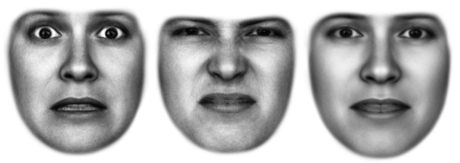

Why do we become saucer-eyed when afraid and taper our eyelids to slits when disgusted?

These near-opposite facial expressions are rooted in emotional responses that exploit how our eyes gather and focus light to detect an unknown threat, found a study by a Cornell neuroscientist. In fear, our eyes widen, boosting sensitivity and expanding our field of vision to locate surrounding danger. When repulsed, our eyes narrow, blocking light to sharpen focus and pinpoint the source of our disgust.

The findings by Adam Anderson, associate professor of human development in Cornell’s College of Human Ecology, suggest that human facial expressions arose from universal, adaptive reactions to environmental stimuli and not originally as social communication signals, lending support to Charles Darwin’s 19th-century theories on the evolution of emotion.

“These opposing functions of eye widening and narrowing, which mirror that of pupil dilation and constriction, might be the primitive origins for the expressive capacity of the face,” Anderson said. “And these actions are not likely restricted to disgust and fear, as we know that these movements play a large part in how, perhaps, all expressions differ, including surprise, anger and even happiness.”

Anderson and co-authors described these ideas in the paper, “Optical Origins of Opposing Facial Expression Actions,” published in the March issue of Psychological Science.

For the experiment, Anderson, with collaborators at the University of Toronto and the University of Waterloo, used standard optometric measures to gauge how light reached the retina as study participants made fearful, disgusted and neutral expressions. Looks of disgust resulted in the greatest visual acuity – less light and better focus; fearful expressions induced maximum sensitivity – more light and a broader visual field.

“These emotions trigger facial expressions that are very far apart structurally, one with eyes wide open and the other with eyes pinched,” said Anderson, the paper’s senior author. “The reason for that is to allow the eye to harness the properties of light that are most useful in these situations.”

What’s more, the paper notes, emotions filter our reality, shaping what we see before light ever reaches the inner eye.

“We tend to think of perception as something that happens after an image is received by the brain,” Anderson said. “But, in fact, emotions influence vision at the very earliest moments of visual encoding.”

Essentially, our eyes are miniature cameras, constructed millennia before humans understood optics, said lead author Daniel Lee, Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto, where Anderson previously taught.

“As automatic actions accompanying our emotions, it means that Mother Nature had solved and programmed within us this fundamental optical principle,” Lee added.

Anderson’s Affect and Cognition Laboratory is now studying how these contrasting eye movements may account for how facial expressions have developed to support nonverbal communication across cultures.

“We are seeking to understand how these expressions have come to communicate emotions to others,” he said. “We know that the eyes can be a powerful basis for reading what people are thinking and feeling, and we might have a partial answer to why that is.”

Ted Boscia is director of communications and media for the College of Human Ecology.