Karl Pillemer, Hazel E. Reed Professor in the Department of Human Development, shared notable financial advice from his surveys of more than 10,000 older adults in this story in USA Today, January 14th. Read more.

Author Archives: ktb1@cornell.edu

Kids may suffer in gap between haves and have-nots

In U.S. counties where personal incomes cluster on opposite sides of the rich and poor spectrum, children appear to endure more neglect and abuse, according to new research by John Eckenrode and colleagues reported in Reuters, February 11th. Using statistical methods to gauge income inequality, the team found a steep rise in the rate of child maltreatment with rising inequality. The relationship held after researchers adjusted for poverty itself, and other factors such as the racial and ethnic makeup of regions, education levels and the number of people receiving public assistance income. Read more.

The ironic adverse effects of expertise

Valerie Reyna, professor of human development, found that intelligence agents were more likely to be biased by the wording or framing of risky choice problems than college students or other adults. Her research is quoted in this story in Psychology Today on January 28th.

Experts tend to rely on gist-based representations of situations rather than instead of verbatim ones, in other words, experts are more likely to think of things in a summarized form rather than think about the exact numbers in a step by step fashion. This helps them to make decisions more quickly and to sort relevant from irrelevant information when making decisions. The downside is that they may be more prone to decision-making biases. Read more.

Study: Facial expressions evolved from optical needs

By Ted Boscia

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, March 20, 2014

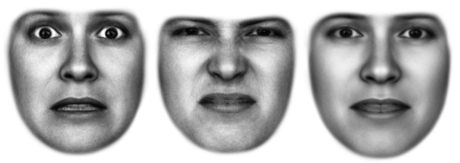

Why do we become saucer-eyed when afraid and taper our eyelids to slits when disgusted?

These near-opposite facial expressions are rooted in emotional responses that exploit how our eyes gather and focus light to detect an unknown threat, found a study by a Cornell neuroscientist. In fear, our eyes widen, boosting sensitivity and expanding our field of vision to locate surrounding danger. When repulsed, our eyes narrow, blocking light to sharpen focus and pinpoint the source of our disgust.

The findings by Adam Anderson, associate professor of human development in Cornell’s College of Human Ecology, suggest that human facial expressions arose from universal, adaptive reactions to environmental stimuli and not originally as social communication signals, lending support to Charles Darwin’s 19th-century theories on the evolution of emotion.

“These opposing functions of eye widening and narrowing, which mirror that of pupil dilation and constriction, might be the primitive origins for the expressive capacity of the face,” Anderson said. “And these actions are not likely restricted to disgust and fear, as we know that these movements play a large part in how, perhaps, all expressions differ, including surprise, anger and even happiness.”

Anderson and co-authors described these ideas in the paper, “Optical Origins of Opposing Facial Expression Actions,” published in the March issue of Psychological Science.

For the experiment, Anderson, with collaborators at the University of Toronto and the University of Waterloo, used standard optometric measures to gauge how light reached the retina as study participants made fearful, disgusted and neutral expressions. Looks of disgust resulted in the greatest visual acuity – less light and better focus; fearful expressions induced maximum sensitivity – more light and a broader visual field.

“These emotions trigger facial expressions that are very far apart structurally, one with eyes wide open and the other with eyes pinched,” said Anderson, the paper’s senior author. “The reason for that is to allow the eye to harness the properties of light that are most useful in these situations.”

What’s more, the paper notes, emotions filter our reality, shaping what we see before light ever reaches the inner eye.

“We tend to think of perception as something that happens after an image is received by the brain,” Anderson said. “But, in fact, emotions influence vision at the very earliest moments of visual encoding.”

Essentially, our eyes are miniature cameras, constructed millennia before humans understood optics, said lead author Daniel Lee, Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto, where Anderson previously taught.

“As automatic actions accompanying our emotions, it means that Mother Nature had solved and programmed within us this fundamental optical principle,” Lee added.

Anderson’s Affect and Cognition Laboratory is now studying how these contrasting eye movements may account for how facial expressions have developed to support nonverbal communication across cultures.

“We are seeking to understand how these expressions have come to communicate emotions to others,” he said. “We know that the eyes can be a powerful basis for reading what people are thinking and feeling, and we might have a partial answer to why that is.”

Ted Boscia is director of communications and media for the College of Human Ecology.

Related Information

Low-income home strife drives earlier teen sex

By Susan S. Lang

Reprinted from the Cornell Chronicle, March 3, 2014

The age at which people become sexually active is genetically influenced – but not when they grow up in stressful, low-income household environments, reports a new study.

“Our study shows that environmental influences – rather than genetic propensities – are more important in predicting age at first sex (AFS) for adolescents from stressful backgrounds, who have few societal and economic resources,” says Jane Mendle, assistant professor of human development in the College of Human Ecology, pointing out that genes determine when teens begin puberty, which is a strong predictor of AFS.

“In fact, genes contribute only negligibly to AFS for these teens. It can almost be thought of as the environment ‘taking over’ the natural developmental trajectory that might occur in a less stressful background,” she adds.

For teens from financially advantaged backgrounds, on the other hand, the environment is much less influential and genes play a more important role in predicting AFS, Mendle notes.

The study, co-authored with University of Texas at Austin researchers, was published online in January in the journal Developmental Psychology.

While many studies have examined either genetic influences or environmental influences on AFS, “ours was one of the very first to consider gene-environment interactions in AFS, or how genetic expression may vary according to environmental circumstances,” Mendle says.

Using a sample of 1,244 pairs of identical twins (who share 100 percent of their genes) and non-twin full siblings (who share 50 percent of their genes) from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, the researchers found that genetic influences on AFS were suppressed among low-socioeconomic-status and ethnic-minority teens compared with higher socioeconomic status and ethnic-majority youth. Father absence did not uniquely moderate genetic influences on AFS.

“And because we looked at identical twins and siblings, we could account for the importance of big family differences – and that enabled us to focus solely on understanding the environmental influences in AFS,” she says.

In addition to genetic influences, the use of twins and siblings in the study design accounted for shared environmental influences, such as religion or certain aspects of parenting, for siblings in the same family and for environmental influences that were unique to each youth.

Their findings “are broadly consistent with previous findings that genetic influences are minimized among individuals whose environments are characterized by elevated risk,” the researchers wrote.

“There has been a lot of dialogue and controversy in America on how to handle adolescent sexuality, and what programs may be most effective in reducing some of the outcomes associated with high-risk sexual behavior in teens,” Mendle says. “Many factors predict whether a teen is sexually active and when he or she transitions to sexual maturity. Our results help us understand in what contexts these factors will be malleable.”

The study, “Early Adverse Environments and Genetic Influences on Age at First Sex: Evidence for Gene x Environment Interaction,” co-authored by Texas researchers Marie D. Carlson and K. Paige Harden, received no outside funding.

Related Information

Adapted arthritis program boosts participation

By Karene Booker

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, February 19, 2014

A low-cost, six-week program that teaches people how to manage pain and stay active has proven to reduce arthritis pain and disability, yet few of the nation’s 50 million adult arthritis sufferers have used it. By enhancing the program’s content and delivery with the help of community partners, Cornell researchers report that attendance improved dramatically, and participants were significantly more likely to stay in the modified program compared to the original, while experiencing the same physical and mental health improvements.

“Effective health programs may not reach people who need them due to factors such as culture, language, age or income, but changing programs to meet the needs of new target populations can make a dramatic difference,” said study co-author Karl Pillemer, professor of human development in Cornell’s College of Human Ecology.

The study, which was published in February in the Musculoskeletal Journal of the Hospital for Special Surgery (Vol. 10:1), focuses on the Arthritis Self-Management Program, also known as the Arthritis Self-Help Course.

“To our knowledge, this is the first controlled study to directly compare the effects of an adapted chronic disease self-management program with the original,” said co-author Dr. M. Carrington Reid, associate professor in geriatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College. He added that rigorously evaluating modified programs such as this one to ensure they still deliver the expected benefits is rare, but critical.

To modify the underutilized program, Reid, Pillemer and his colleagues collaborated with a team of staff from local agencies and senior centers, older adults and program instructors. The team incorporated nearly 40 enhancements suggested by program participants and instructors, such as adding in-class exercise practice and individual action plans to make use of local health programs, expanding information on healthy eating and weight management, and simplifying reading materials.

The adapted and original versions were tested with 201 older adults, with baseline data collected at the beginning, at program completion and 18 weeks later. While both groups experienced equivalent relief in pain, stiffness and perceived disability, attendance in the adapted program improved by 46 percent, and participants were 26 percent more likely to stay in the modified program than in the original.

That means that the modified program could have significantly more reach and impact, the authors say. Their findings not only underscore the value of involving local stakeholders in tailoring interventions to specific populations, but also the importance of conducting controlled experiments to quantify the results, they say. Furthermore, they add, their findings highlight the potential of relatively simple programs to help build self-efficacy for arthritis management and improve quality of life.

The study, “Measuring the Value of Program Adaptation: A Comparative Effectiveness Study of the Standard and a Culturally Adapted Version of the Arthritis Self-Help Program,” was also co-authored by graduate student Emily Chen and senior research associate Charles Henderson of Cornell, and Samantha Parker of Tulane University School of Medicine. It was supported in part by the National Institute of Nursing Research and the National Institute on Aging.

Karene Booker is an extension support specialist in the Department of Human Development.

Related Information:

Child abuse and neglect rise with income inequality

By H. Roger Segelken

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, February 11, 2014

In the aftermath of the Great Recession and the increased attention to the widening income gap, concern over the impact of inequality on children and families has risen. According to a nationwide study by Cornell researchers, the list of bad outcomes associated with income inequality now includes child abuse and neglect.

The income inequality-child maltreatment study, covering all 3,142 U.S. counties from 2005 to 2009, is said to be the most comprehensive of its kind and the first to link higher risk of child maltreatment to localities where the gap between rich and poor is greatest.

“More equal societies, states and communities have fewer health and social problems than less equal ones – that much was known. Our study extends the list of unfavorable child outcomes associated with income inequality to include child abuse and neglect,” said John Eckenrode, professor of human development and director of the Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research in the College of Human Ecology.

Results of the nationwide study were published in the Feb. 10 online edition of the journal Pediatrics as “Income Inequality and Child Maltreatment in the United States.” In addition to Eckenrode, who directs the National Data Archive of Child Abuse and Neglect, other report authors include Elliott Smith, Margaret McCarthy and Michael Dineen, researchers in Cornell’s Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research.

Nearly 3 million children younger than 18 years of age are abused physically, sexually or emotionally or are physically neglected each year in the United States, the Cornell researchers noted. That is about 4 percent of the youth population.

“We have known for some time that poverty is one of the strongest precursors of child abuse and neglect,” Eckenrode said. “In this paper we were also interested in areas with wide variations in income – think of counties encompassing affluent suburbs and impoverished inner cities – and in the U.S. there is quite a lot of variation in inequality from county to county and state to state.”

The damage inflicted on children by maltreatment doesn’t stop when kids graduate – if they do – from school, the Cornell researchers observed. “Child maltreatment is a toxic stressor in the lives of children that may result in childhood mortality and morbidities and have lifelong effects on leading causes of death in adults,” they wrote. “This is in addition to long-term effects on mental health, substance use, risky sexual behavior and criminal behavior ... increased rates of unemployment, poverty and Medicaid use in adulthood.” Eckenrode noted that “reducing poverty and inequality would be the single most effective way to prevent maltreatment of children, but in addition there are proven programs that work to support parents and children and help to reduce the chances of abuse and neglect – clearly a multifaceted strategy is needed.”

Support for the study came from the Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Related Information

Book highlights memory’s role as social glue

By Karene Booker

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, March 3, 2014

Memory’s crucial impact on our ability to establish and maintain social bonds is the focus of a new book, “Examining the Role of Memory in Social Cognition” (Frontiers), edited by Cornell neuroscientist Nathan Spreng.

“The book brings together the first research on the linkages between memory and social behavior, processes traditionally studied separately,” said Spreng, assistant professor of human development and the Rebecca Q. and James C. Morgan Sesquicentennial Faculty Fellow in Cornell’s College of Human Ecology.

“Remembering our own past and interpreting other people’s thoughts and feelings both activate similar neural pathways in the brain – a connection that may help us translate our personal experience into understanding others and navigating the complex dynamics of human social life,” he said.

“Discovery of the overlapping brain networks provided a clue about memory’s vital role in social interaction and inspired development of this first book on the topic,” he added.

In the book, neuroscientists and psychologists discuss their latest findings on topics such as how neural networks affect social abilities; how memory influences empathy; how aging affects memory and social abilities; how memory and social abilities are impacted by disorders such as schizophrenia and autism; and how amnesia and other memory impairments affect social abilities.

Intended for researchers and students in the fields of social and cognitive neuroscience, the book is a starting point for a line of cross-disciplinary research that may one day provide insights into how to improve social skills like empathy in healthy and impaired individuals, Spreng said.

Karene Booker is extension support specialist in the Department of Human Development.

Related Information

New institute focuses on human brain research

By Karene Booker

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, February 13, 2014

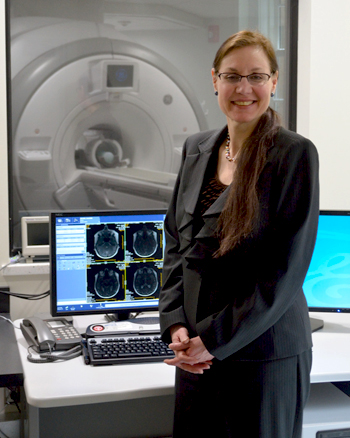

The new Human Neuroscience Institute in Cornell’s College of Human Ecology aims to advance research on the neural basis of human behavior.

“Prioritizing the word ‘human’ in the name of the institute underlines the common commitment to human development,” said Valerie Reyna, director of the institute and co-director of the Cornell MRI Facility. The focus of the institute – to better understand how brain systems drive cognition and behavior – has broad implications for enabling people to lead happier and more fulfilling lives, she said.

Cornell scientists can now observe on campus which areas of the brain fire when we think, react and decide, thanks to a 3-tesla MRI machine in the Cornell MRI Facility in Martha Van Rensselaer Hall that has been in place since 2012. Ready access to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) gives researchers more power to ask novel questions and test psychological and behavioral science theories with new data, said Reyna, professor of human development. She is leading the first National Institutes of Health-funded study in the facility: A team of economists, psychologists and neuroscientists are using the tool to better understand how teens and adults process emotions, gauge risks and make decisions.

“A lot of psychology traditionally relies on self-report,” Reyna explained. “With the advent of fMRI, brain scan data can be integrated with other data – behavioral, social and ecological – to shed light on the mechanisms driving behavior. We can look at the brain from the micro neurochemistry level to the macro social level, bringing basic research to bear on important human problems.”

But to conduct human neuroscience research and extract meaningful data from the images, far more than an accessible MRI machine is required, Reyna said.

So the new institute is developing other essential research services and tools – such as powerful computing – with a core group of neuroscientists in the Department of Human Development whose aim is to facilitate research, education and outreach in human neuroscience and, ultimately, to inform interventions that improve health and well-being.

The institute’s faculty affiliates are: Adam Anderson, Charles Brainerd, Eve De Rosa and Nathan Spreng. Anderson, associate professor, explores the psychological and neural underpinnings of emotions – what they are, how they are generated in the brain, and how we regulate them. Brainerd, professor, examines how normal aging and disease affect cognitive processes, focusing on factors associated with brain atrophy and memory decline in mild cognitive impairment and dementia. De Rosa, associate professor, uses neuroimaging and behavioral measures in humans and additional measures in rats to study learning and attention, with a focus on the role of the neurochemical acetylcholine. Spreng, assistant professor, uses fMRI to study large-scale brain networks, how these systems interact to support complex cognition and how patterns of brain activity change with advancing age.

Each of these scientists works at the frontiers of basic science, Reyna noted, but they also translate fundamental discoveries about brain function into ways to improve human well-being across the lifespan.

The nuts and bolts of MRI technology

The key advantage of magnetic resonance imaging is that it allows researchers to see inside living tissues, providing detailed pictures of internal structures without using invasive procedures or ionizing radiation. An array of specialized techniques allows scientists to visualize blood flow, the movement of water, the presence and concentration of various organic molecules, moving tissue in real time, and more.

The core of a magnetic resonance imaging machine is made up of coils of wire though which electricity is passed to create a magnetic field, which aligns the spins of hydrogen protons in the water abundant in living things, including humans.

A coil fit specifically for the body part being imaged transmits pulses of radiofrequency waves, causing some of the hydrogen protons to absorb the energy and temporarily change their spins. When the pulse is turned off, they return to their prior state, giving off an energy signal that the coils detect and send to the MRI computer. During imaging, additional small gradient magnetic fields encode this signal with spatial location. A map of the internal tissues can be reconstructed from the signal since protons in different tissues return to equilibrium at different rates.

To visualize neural activity in the brain, researchers often use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which generates images of brain activity in response to performing different tasks.

The most common fMRI method detects changes in blood flow when activated areas of the brain are recharged by fresh blood rich in oxygen and glucose. Oxygen-rich blood has different magnetic properties than oxygen-poor blood, and these differences can be measured and mapped to provide a picture of brain activity. The resulting images require complex processing and statistical analyses to extract meaningful data – the work of computing resources connected to the MRI machine.

Karene Booker is an extension support specialist in the Department of Human Development.

Related Information

Study: Ads can influence ‘smart’ false memories

By Ashlee McGandy

Reprinted from Cornell Chronicle, March 18, 2014

It is commonly believed that false memories – recollections that are factually incorrect – occur because something goes wrong in the brain. However, recent research shows that some false memories are formed by overthinking rather than deficient processing. In a new study, Cornell researchers examined how advertising can result in these “smart” false memories, where consumers who have a propensity to think more about decisions produce more false memories than those who process information at a more superficial level. The study was published in the January/February issue of the Journal of Advertising.

“I’ve been researching false memories for 15 or 20 years. The assumption is always that false memories happen because something goes wrong – some deficiency in processing. The research shows that is not necessarily true,” said co-author Kathy LaTour, associate professor of services marketing at the School of Hotel Administration (SHA).

“The same deficiency assumption dominates the law’s view of the memory errors that witnesses often make,” added co-author Charles Brainerd, professor and department chair in human development in the College of Human Ecology.

The “smart” false memories examined in the study are explained by fuzzy-trace theory (FTT), which was developed by Brainerd and Valerie Reyna, Cornell professor of human development and psychology, in response to the assumption that people who process experiences superficially or have deficient processing abilities due to age are more likely to succumb to false memories. FTT, instead, suggests that false memories can occur when there is greater processing involved, and individuals elaborate on what they actually see and hear.

“This is the first time ‘smart’ false memories have been studied in an advertising context,” said Michael LaTour, visiting professor of services marketing at SHA and the third author of the study. “Dr. Brainerd’s fuzzy-trace theory provides a rich foundation for tackling these complex phenomena.”

In three experiments, the authors identified several implications for the advertising industry.

Consumers who are more likely to form “smart” false memories use cues to build stories and better understand their experiences. “Advertisers then might consider using abstract messages that engage consumers with their elaborative processes and providing cues that direct how they want their consumers to interpret their experiences,” the authors write.

For example, a soda company might use cues to reinforce the experience of holding a cool glass bottle of effervescent soda in an ad that shows a fun family experience. Consumers may not remember the specific cues, but those with a tendency to form “smart” false memories will come to associate the soda with the cool freshness involved in opening the bottle.

Conversely, simpler and more direct advertising messages should be used for consumers who may be too distracted to engage with the ads, such as consumers surfing the Internet. In these cases, showing the soda company logo could be a more effective than trying to get consumers to engage with a deeper experience.

Finally, in the past, there have been calls for public policy actions to protect particularly vulnerable consumers – such as young children, the elderly or mentally disabled – from deceptive marketing practices that can create false memories. The new research on “smart” false memories finds that these groups are actually less susceptible than consumers who overthink the advertising messages. In practice, advertisers do not necessarily want to suggest false information but rather implant cues that can help reshape the conversation about their brand.

“False memories are not necessarily a bad thing. The reconstructive process of memory is natural, and ads influence that process. Memory is not a video tape, and advertising is not mind control,” said Kathy LaTour.

The study, “Fuzzy Trace Theory and ‘Smart’ False Memories: Implications for Advertising,” received no outside funding.

Ashlee McGandy is a staff writer for the School of Hotel Administration.