Some people are genetically predisposed to see the world darkly, according to a study from the laboratory of a researcher now on the faculty of Cornell’s College of Human Ecology.

Adam K. Anderson, associate professor of human development, is continuing his research on emotions, genetics and perception, which began at his laboratory at the University of Toronto in collaboration with scientists at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Their study, published in September in Psychological Science, found a previously known gene variant causing some individuals to perceive emotional events – especially negative ones – more acutely than others.

“This genetic variation contributes to how emotions bias individuals to see the same world in different ways,” says Anderson. “More than just how we may later remember, these findings suggest genetics influence how our brains pick and choose which events to perceive in the first place.”

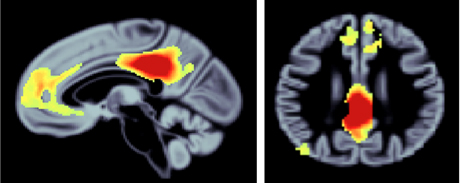

The gene in question is the ADRA2b deletion variant, which influences the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. Previously found to play a role in the formation of emotional memories, the new study shows that the ADRA2b deletion variant also plays a role in real-time perception.

Some 200 study participants were shown positive, negative and neutral words in a rapid succession, each at 1/10th of a second. While all individuals perceived positive words better than neutral words, participants with the ADRA2b gene variant were more likely to perceive negative words than others.

“These individuals may be more likely to pick out angry faces in a crowd of people,” says Rebecca M. Todd of UBC’s Department of Psychology. “Outdoors, they might notice potential hazards – places you could slip, loose rocks that might fall – instead of seeing the natural beauty.”

The findings shed new light on ways in which genetics – combined with other factors such as education, culture and moods – can affect individual differences in emotional perception and human subjectivity, the researchers say.

Future work on this topic in Anderson’s laboratory intends to examine whether individuals with these very same genetic variants, depending on their environment and stage of development, can be coaxed to enhance perception of the positive rather than the negative.

The study, “Genes for Emotion-Enhanced Remembering Are Linked to Enhanced Perceiving,” was funded in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

![Biennial Urie Bronfenbrenner Conference [BCTR]](https://hdtoday.human.cornell.edu/files/2013/10/AgingConf1-1j2gh6j.jpg)