Reprinted from Human Ecology Magazine, Spring 2016

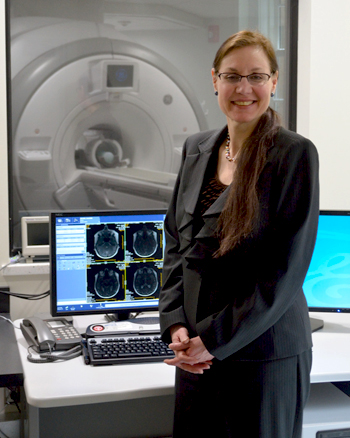

In the Department of Human Development, fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) informs Nathan Spreng’s studies of large-scale brain network dynamics and their role in cognition.

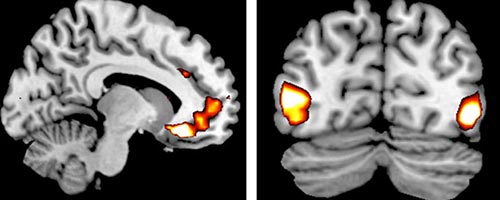

A Rebecca Q. and James C. Morgan Sesquicentennial Faculty Fellow, Spreng is curious about how volunteer test subjects in his Laboratory of Brain and Cognition conceive of the future and how they navigate the social world. Then there’s the hypothesized link between thinking about the past and imagining the future. “These different cognitive tasks activate similar brain regions,” Spreng

explains. “But it’s actually the other regions they talk to that help determine whether we’re thinking about the past or the future.”

It’s not only when the brain is doing something—performing cognitive tasks—that’s interesting to Spreng. Neuroscientists also study brain activity while people are simply resting in the scanner. But do our brains ever truly “rest”?

Not according to Spreng: “Signaling is always going on up there. Understanding how different brain regions hum along together (or are connected functionally) while people are simply resting can tell us a lot about how their brains work during cognitive tasks, and might eventually help us predict how resilient they will be to aging or brain disease.”

Spreng believes there’s even more in the resting-state fMRI data than previously imagined. In collaboration with Peter Doerschuk, professor of biomedical engineering, Spreng is developing a new method for analyzing resting-state activity. Doerschuk, also a Harvard-educated medical doctor, excels at developing algorithms for high-performance software systems.

In published reports of their progress so far, Spreng and Doerschuk say they’re finding ways to add important new details to the map of the resting brain— details like causality and direction of information flow between regions. Cause

and signaling direction are important considerations, Spreng notes, “when characterizing exactly how that network operates, and how information flows through the system, and how it might be involved in cognitive functions.”

The Cornell collaborators say their new statistical method shows promise in tracking both causation and direction of neural signals, showing us that the resting brain is anything but.