Loading...

Loading...

Literature review report – Youth Risk Perception and Decision-Making Related to Health Behaviors in the COVID-19 Era

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Valerie Reyna, professor of human development, studies the neuroscience of risky decision making and its implications for health and well-being. She says changing advice contributes to the perception that experts might not know what they are doing, which is false. Emotions and actions in reaction to a risk depend crucially on how people understand the gist of the risk. Providing the facts is important, but it is how people interpret those facts that determine behavior. Dr. Reyna participated in a Newswire roundtable of experts (click here for the link to the video) and discussed how her research can help the public better understand the risks of COVID-19 and improve their decisions about how to respond to it. She also participated in a roundtable discussion organized by the Association for Psychological Science (click here for the link to the transcript).

During the COVID-19 crisis, the public’s need for accurate scientific information is a matter of life and death. Nevertheless, misinformation is plentiful and it competes with scientific information in what Reyna calls “a battle for the gist” in a new PNAS publication.

In an age of evidence-based science communications for the public good, researchers face a persistent paradox. Despite their efforts to report research findings to the public, misinformation propagates across the Web and around the world. Outreach campaigns using traditional fact-based communications are not necessarily effective in correcting misconceptions. What can be done to more effectively communicate science in a way that helps the public resist misinformation?

Valerie Reyna, Lois and Melvin Tukman Professor of Human Development at Cornell University, has applied her information-processing model, Fuzzy Trace Theory (FTT) to the puzzle of why people accept alternative explanations, narratives, interpretations, or conspiracy theories, and discount or distort facts. All human beings tend to distort facts. However, it is possible to help people make decisions that draw on scientific facts and that reflect personal values. The FTT approach offers a framework to understand and to reduce obstacles to public understanding of scientific research. Reyna has identified several key components necessary for constructing an accurate representation of the meaning of science communications.

According to the FTT model, as we process information, it is encoded simultaneously in two formats – “gist” and “verbatim.” Verbatim information includes specific facts, details, numbers, and exact quantities. The precise details, percentages, proportions, or ratios can represent facts, but typical scientific communications do not necessarily convey the relevance or substance of facts: its bottom-line meaning. Rote memory for detailed information often fades from memory, whereas memory for gist—or substance--endures.

Gist representations of information in the mind elicit emotions and social values, and are shaped by knowledge and experience. Research has shown that long after verbatim content, (e.g., specific words, numbers, or syntax), has faded from memory, gist memory remains preserved.

The discrepancy between the recall of gist information and the recall of verbatim information offers an inroad to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories. The effort to provide objective unbiased facts often leads researchers to present data largely in a verbatim format, allowing recipients to judge for themselves the truth-value and justification of the data. This verbatim approach opens the door to others to offer interpretations and explanations, even when the science is uncertain. Hence, meaningful, emotional, and values-evoking alternative gist interpretations or narratives can gain traction and spread across the internet or similar media. Individuals can unintentionally misconstrue the verbatim details of the data and share it with others.

The repetition of these messages within a community of sharers and recipients adds credibility to interpretations as the precise verbatim details are increasingly forgotten in favor of the gist content of the misinformation. Thus, Reyna explains that rather than removing all interpretation, emotion, and values, that scientists can communicate in a way that is neither meaningless facts nor persuasion. The meaning behind the gist—the why—should be made as transparent as possible so that individuals can make their own decisions. The gist-based approach to science communications builds on a foundation of science literacy and the value of scientific research for the public, as well as reduces the acceptance and spread of misinformation.

Journal reference for this story:

Reyna, V.R. (2020). A scientific theory of gist communication and misinformation resistance, with implications for health, education, and policy, PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences). www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1912441117

Valerie Reyna is collaborating with Holly Prigerson of Cornell Weill Medical College on an intercampus palliative care project as part of the recently established Academic Integration Initiative which fosters research between the Cornell Ithaca and the Cornell Weill New York City campuses. Dr. Prigerson has been researching factors that hinder communications between patients and physicians about end-of-life decisions. In the course of her research, Prigerson discovered Dr. Reyna's fuzzy trace theory (FTT) and was eager to find a way to collaborate (read more in the downloadable article below). According to Reyna, an important principle of FTT is the "gist principle" which is a type of mental representation that "captures the bottom-line meaning of information, and it is a subjective interpretation of information based on emotion, education, culture, experience, worldview, and level of development" and can be applied to improve doctor-patient understanding and treatment options (click on the title of Dr. Reyna's paper, "A Theory of Medical Decision Making and Health: Fuzzy Trace Theory" to read more about FTT).

Loading...

Loading...

'Mortal Matters' by Anne Machalinski, Weill Cornell Medicine Magazine - Summer 2018.

By Nora Rabah, Allison M. Hermann, Thomas W. Craig, and David Garavito

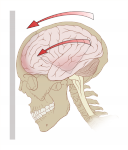

David Garavito, graduate student in the Law, Psychology, and Human Development Program, under the supervision of Dr. Valerie Reyna, is working with communities in New York and around the country with support from an Engaged Cornell grant for student research. He is working with coaches and student athletes to study the effects of concussions on decision making about risks. For his dissertation research, Garavito is developing a model based upon Dr. Reyna’s Fuzzy Trace Theory (FTT) which integrates research on Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), behavioral economics and decision making, and neuroscience to study the perception of risks associated with sports-related concussions among people vulnerable to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

David Garavito, graduate student in the Law, Psychology, and Human Development Program, under the supervision of Dr. Valerie Reyna, is working with communities in New York and around the country with support from an Engaged Cornell grant for student research. He is working with coaches and student athletes to study the effects of concussions on decision making about risks. For his dissertation research, Garavito is developing a model based upon Dr. Reyna’s Fuzzy Trace Theory (FTT) which integrates research on Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), behavioral economics and decision making, and neuroscience to study the perception of risks associated with sports-related concussions among people vulnerable to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Garavito and undergraduates in the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making are working with a growing number of students, coaches, and administrators from high schools and colleges in New York (including Watkins Glen and Moravia high schools, Cornell University, and Ithaca College), Colorado, and Minnesota. Engagement with sports communities has provided the team with the opportunity to educate--and listen to-- the public about current research on concussions and how values or principles can affect perceptions and decisions about concussion risk. Garavito has found that coaches are very supportive of research projects that aim to help keep athletes safe and further knowledge about concussions. Many athletes have enthusiastically agreed to volunteer in Garavito’s studies. The student team also has been working with the Ithaca Youth Bureau and the experiences of coaches and educators at the center have been essential in the development of interactive activities to teach youth about the brain and concussions. The ultimate goal of the concussion intervention is to strengthen healthy values and educate people about risks, and the importance of reporting symptoms of concussions.

Garavito and undergraduates in the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making are working with a growing number of students, coaches, and administrators from high schools and colleges in New York (including Watkins Glen and Moravia high schools, Cornell University, and Ithaca College), Colorado, and Minnesota. Engagement with sports communities has provided the team with the opportunity to educate--and listen to-- the public about current research on concussions and how values or principles can affect perceptions and decisions about concussion risk. Garavito has found that coaches are very supportive of research projects that aim to help keep athletes safe and further knowledge about concussions. Many athletes have enthusiastically agreed to volunteer in Garavito’s studies. The student team also has been working with the Ithaca Youth Bureau and the experiences of coaches and educators at the center have been essential in the development of interactive activities to teach youth about the brain and concussions. The ultimate goal of the concussion intervention is to strengthen healthy values and educate people about risks, and the importance of reporting symptoms of concussions.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a form of dementia, like Alzheimer’s, which results in an accumulation of tau proteins in the brain, however, the onset and progression of CTE is related to a history of concussions. Athletes in contact sports are particularly vulnerable to CTE because many athletes fail to report concussions and their symptoms – a very risky decision that could result in brain damage and cognitive impairment. Using the FTT framework, Garavito and his team of undergraduates are studying this underreporting phenomenon.

Although current research on the underreporting of concussions has brought about the creation of laws mandating concussion education nationwide, research based on FTT has shown that not all education programs are equal. How people process information can have a profound effect on how they make decisions (Mills, Reyna, Estrada, 2008; Widmer, Wolfe, Reyna et al., 2015). Dr. Reyna’s research has shown that adolescents are more likely to rely on verbatim, surface-level details, whereas adults tend to rely on qualitative reasoning and the bottom-line gist of information (Reyna & Farley, 2006; Reyna, Estrada, DeMarinis et al., 2011). For example, if told an athlete has a 2/3 chance of having another concussion if they go back out on the field after having had a concussion on the same day, adolescents make their decisions about risk by considering the numbers and take the chance in order to play more sports because the benefits, to them, outweigh the risks. Adults, on the other hand, get the point that the mere possibility of a catastrophic injury, no matter how small, of getting another concussion (which could result in permanent brain damage or death), is not worth the risk for more playing time. This difference in information processing has not been studied in the underreporting or the perception of risks in sports-related injuries.

Many educational programs emphasize the acquisition of verbatim fact-based knowledge in the hope that these details will help the public understand and make better decisions. Unfortunately, this can lead to the opposite effect – giving people more detailed information causes them to engage in greater precise deliberation and leads them to take unnecessary risks. Football players, for example, may know verbatim facts about the symptoms of concussions, but still “gamble” by not reporting their symptoms, instead of choosing the “sure thing” of being safe and reporting them. This risky decision-making among athletes, in turn, is exacerbated by impairment from prior concussions.

Currently, Garavito, Dr. Reyna, and their team of undergraduates, are using scales based on FTT, to test several important hypotheses. These scales are sensitive measures that can detect if a person is relying more on categorical than fact-based thinking. Fuzzy Trace Theory predicts that categorical or gist-based thinking is more developmentally advanced and can deter people from taking dangerous risks. Garavito hypothesizes that adolescents affected by cumulative concussions may rely less on categorical thinking than non-concussed adolescents. This could lead concussed adolescents to engage in greater risk-taking, in general. Garavito and Reyna are studying whether FTT measures can cue developmentally advanced categorical thinking. Cuing adolescents to engage in categorical thinking will lead them to approach dangerous risks like adults, and is consistent with Dr. Reyna’s research on other types of risk-taking behavior (Reyna, Wilhelms, McCormick et al., 2015).

Nora Rabah is a Biology and Society major in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Allison M. Hermann is the Research and Outreach Manager for the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making.

Thomas W. Craig is the Law, Psychology and Human Development Program Assistant.

David Garavito is a graduate student in the Law, Psychology, and Human Development Program at the College of Human Ecology.

For juries awarding plaintiffs for pain and suffering, the task is more challenging – and the results more inconsistent – than awarding for economic damages, which is formulaic. Now, Cornell social scientists show how to reduce wide variability for monetary judgments in those cases: Serve up the gist.

As an example of gist, juries take into account the severity of injury and time-scope. In the case of a broken ankle, that injury is a temporary setback that can be healed. In an accident where someone’s face is disfigured, the scope of time lasts infinitely and affects life quality. In short, “meaningful anchors” – where monetary awards ideally complement the context of the injury – translate into more consistent dollar amounts.

“Inherently, assigning exact dollar amounts is difficult for juries,” said Valerie Reyna, professor of human development. “Making awards is not chaos for juries. Instead of facing verbatim thoughts, juries rely on gist – as it is much more enduring. And when we realize that gist is more enduring, our models suggest that jury awards are fundamentally consistent.”

The foundation for understanding jury awards lies in the “fuzzy trace” theory, developed by Reyna and Charles Brainerd, professor of human development. The theory explains how in-parallel thought processes are represented in your mind. While verbatim representations – such as facts, figures, dates and other indisputable data – are literal, gist representations encompass a broad, general, imprecise meaning.

“Experiments have confirmed the basic tenets of fuzzy trace theory,” said Valerie Hans, psychologist and Cornell professor of law, who studies the behavior of juries. “People engage in both verbatim- and gist-thinking, but when they make decisions, gist tends to be more important in determining the outcome; gist seems to drive decision-making.”

In addition to authors Reyna and Hans for the study, “The Gist of Juries: Testing a Model of Award and Decision Making,” the other co-authors include Jonathan Corbin Ph.D. ’15; Ryan Yeh ’13, now at Yale Law School; Kelvin Lin ’14, now at Columbia Law School; and Caisa Royer, a doctoral student in the field of human development and a student at Cornell Law School.

The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Cornell’s Institute for the Social Sciences, the Cornell Law School and Cornell’s College of Human Ecology.

Update: On Sept. 1, 2015, the National Science Foundation awarded a grant for $389,996 to Cornell for support of the project “Quantitative Judgments in Law: Studies of Damage Award Decision Making,” under the direction of Valerie P. Hans and Valerie F. Reyna.

Flip a coin, roll the dice, pick a number, throw a dart -- there is no shortage of metaphors for the perceived randomness of juries. That belief that "anything can happen," is applied to some extent to the whole jury model, but nowhere more so than on the topic of civil damages. When jurors are asked to supply a number, particularly on the categories that are intangible (like pain and suffering) or somewhat speculative (like lost earnings), the eventual number is sometimes treated as a kind of crapshoot. What's more, the process that the jury goes through to get to it is seen as a kind of black box: not well understood or necessarily subject to clear influence.

What litigators might not know is that the subject of civil damages is a great example of social science research beginning to close the gap. Based on research within the last decade, we are coming closer to opening that black box in order to see a jury process -- albeit not fully predictable, but at least more knowable. The way jurors arrive at a number is increasingly capable of being described through the literature, and these descriptions have implications for the ad damnum requests made by plaintiffs and for the alternative amounts recommended by defendants. A study just out this year (Reyna et al., 2015), for example, provides support for a multistage model describing how jurors move from a story, to a general sense or 'gist' of damages, and then to a specific number. Their work shows that, while the use of a numerical suggestion -- an 'anchor' -- has a strong effect on the ultimate award amount, that effect is strongest when the anchor is meaningful. In other words, just about any number will have an effect on a jury, but a meaningful number -- one that provides a reference point that matters in the context of the case -- carries a stronger and more predictable effect. This post will share some of the results from the new study framed around some conclusions that civil litigators should take to heart.

The research team, led by Cornell psychologists Valerie Reyna and Valerie Hans, begins with the observation that "jurors are often at sea about the amounts that should be awarded, with widely differing awards for cases that seem comparable." They cover a number of familiar reasons for that: limited guidance from the instructions; categories that are vague or subjective; judgments that depend on broad estimations, if not outright speculation; and a scale that begins at zero but, theoretically at least, ends in infinity. Add to that the problem that jurors often have limited numerical competence (low "numeracy") or an aversion to detailed thinking (low "need for cognition"). All of that means that there isn't, and will never be, a precise and predictable logic to a jury's damages award. But it doesn't mean that they're picking a number out of a hat either. Research is increasingly pointing toward the route jurors take in moving to the numbers.

As detailed in the article, jury awards will vary on the same essential case facts, but a number of studies have found a strong "ordinal" relationship between injury severity and award amounts: More extreme injuries lead to higher awards, and vice versa. Increasing knowledge of the process has led researchers to describe a jury's decision in steps, both to better understand it, and also to underscore that some steps are more predictable than others. The following model, for example, is drawn from Hans and Reyna's 2011 work (though I've taken the liberty to make some of the language less academic):

That breakdown of steps is backed up by the research reviewed in the article, but it isn't just useful for scholars. Watch mock trial deliberations and you are likely to see jurors moving through that general sequence. Knowing that jurors are going to implicitly or explicitly settle on a 'gist' (large, small, or in between) before translating that into a specific number is also helpful to litigators in providing the reminder 'speak to the gist' as well as to the ultimate number.

The model also points out the advantages of giving jurors guidance on a number. Research supports the view that it is a good idea to try to anchor jurors' awards by providing a number. Suggesting a higher number generally leads to a higher award, and vice versa. Reyna and colleagues found that even the mention of an arbitrary dollar amounts (the cost of courthouse repairs) influences the size of awards. But the central finding of the study is that it helps even more if the dollar amount isn't arbitrary. "Providing meaningful reference points for award amounts, as opposed to only providing arbitrary anchors," the team concludes, "had a larger and more consistent effect on judgments." Not only are the ultimate awards closer to the meaningful anchor, but they are also more predictable, being more tightly clustered around the anchor when that anchor is meaningful and not arbitrary.

Of course, the notion of what is "meaningful" might carry just as much vagueness as the damages category itself, and the research team is not fully explicit on what makes a number meaningful in a trial context. That might be a fitting question for the next study, but in the meantime, the team gives at least some guidance. To Reyna et al., recommended amounts are "meaningful in the sense that their magnitude is understood as appropriate in the context of that case." In the study, the "meaningful" anchor was that one that expressed a pain and suffering amount as being either higher or lower than one year's income. That's not a perfect parallel -- one is payment for work, the other is recompense for suffering -- but it does reference something that the jury is used to thinking about and using as a rough way of valuing time. By nature, meaningful anchors will vary from case to case, but there are a few general numbers that could be used as a reference point, like median annual salary; daily, weekly, or monthly profits; or remediation costs.

Of course, those are well-known devices that attorneys will regularly apply. Still, it is good to know that, at a preliminary level at least, they have the social science stamp of approval. Those kinds of anchors and reference points work because they give jurors a way to get a gist of the claimed damages, and a way to bring abstract numbers into the jurors' own mental universe.