The Cornell Chronicle, April 13, 2017.

By Stephen D'Angelo

New research by Adam Anderson, professor of human development at Cornell’s College of Human Ecology, reveals why the eyes offer a window into the soul.

According to the recent study, published in Psychological Science Feb. 1, Anderson found that we interpret a person’s emotions by analyzing the expression in their eyes – a process that began as a universal reaction to environmental stimuli and evolved to communicate our deepest emotions.

For example, people in the study consistently associated narrowed eyes – which enhance our visual discrimination by blocking light and sharpening focus – with emotions related to discrimination, such as disgust and suspicion. In contrast, people linked open eyes – which expand our field of vision – with emotions related to sensitivity, like fear and awe.

“When looking at the face, the eyes dominate emotional communication,” Anderson said. “The eyes are windows to the soul likely because they are first conduits for sight. Emotional expressive changes around the eye influence how we see, and in turn, this communicates to others how we think and feel.”

This work builds on Anderson’s research from 2013, which demonstrated that human facial expressions, such as raising one’s eyebrows, arose from universal, adaptive reactions to one’s environment and did not originally signal social communication.

Both studies support Charles Darwin’s 19th-century theories on the evolution of emotion, which hypothesized that our expressions originated for sensory function rather than social communication.

“What our work is beginning to unravel,” said Anderson, “are the details of what Darwin theorized: why certain expressions look the way they do, how that helps the person perceive the world, and how others use those expressions to read our innermost emotions and intentions.”

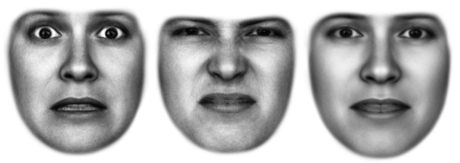

Anderson and his co-author, Daniel H. Lee, professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of Colorado, Boulder, created models of six expressions – sadness, disgust, anger, joy, fear and surprise – using photos of faces in widely used databases. Study participants were shown a pair of eyes demonstrating one of the six expressions and one of 50 words describing a specific mental state, such as discriminating, curious, bored, etc. Participants then rated the extent to which the word described the eye expression. Each participant completed 600 trials.

Participants consistently matched the eye expressions with the corresponding basic emotion, accurately discerning all six basic emotions from the eyes alone.

Anderson then analyzed how these perceptions of mental states related to specific eye features. Those features included the openness of the eye, the distance from the eyebrow to the eye, the slope and curve of the eyebrow, and wrinkles around the nose, the temple and below the eye.

The study found that the openness of the eye was most closely related to our ability to read others’ mental states based on their eye expressions. Narrow-eyed expressions reflected mental states related to enhanced visual discrimination, such as suspicion and disapproval, while open-eyed expressions related to visual sensitivity, such as curiosity. Other features around the eye also communicated whether a mental state is positive or negative.

Further, he ran more studies comparing how well study participants could read emotions from the eye region to how well they could read emotions in other areas of the face, such as the nose or mouth. Those studies found the eyes offered more robust indications of emotions.

This study, said Anderson, was the next step in Darwin’s theory, asking how expressions for sensory function ended up being used for communication function of complex mental states.

“The eyes evolved over 500 million years ago for the purposes of sight but now are essential for interpersonal insight,” Anderson said.

![Biennial Urie Bronfenbrenner Conference [BCTR]](https://hdtoday.human.cornell.edu/files/2013/10/AgingConf1-1j2gh6j.jpg)