Reprinted from College of Human Ecology's Alumni Profiles

by Stephen D'Angelo

Lindsay Dower ‘17 spent her four years at Cornell working to improve the lives of both those within the College of Human Ecology and in the broader Ithaca community, truly embodying the mission of the college.

As a Human Development major and Policy Analysis and Management minor, working towards a career in health policy, she pursued coursework that allowed her to better understand the human condition in the context of healthcare. Lindsay took full advantage of the opportunities within the college to create an undergraduate experience that intertwined courses in behavioral neuroscience with those in healthcare.

She joined Professor Valerie Reyna’s lab for Rational Decision Making during her freshman year after learning about Reyna’s work in an introductory Human Development course. Further, Lindsay served as a Cornell Cooperative Extension Intern during the summer of 2014, bringing evidence-based curricula developed in the lab to middle school-aged campers at 4-H Camp Bristol Hills. Through a series of hands-on activities, she delivered an obesity prevention intervention to the campers, while completing a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of the curricula.

The following year, she gratefully received a Human Ecology Alumni Association Grant to continue studying how people make decisions about their eating and exercise habits. Lindsay’s research then expanded to include a project on investigating the decision making behind medication adherence in Type I and Type II diabetics. Her passion for the projects in the lab earned Lindsay the role of Undergraduate Team Leader of the Health and Medical Decision Making Team when she was a junior. Lindsay led a group of over ten undergraduates in the lab, serving as a resource to help them engage with the material in meaningful ways.

Outside of the classroom, Lindsay was very involved with Alpha Phi Omega, a national community service fraternity with a chapter on campus. As a member of APO, Lindsay served as chair for the Loaves and Fishes project, during which she and other members volunteered to serve free, hot meals to those who needed them most in downtown Ithaca. Additionally, she played the flute in the Big Red Pep Band during her time at Cornell.

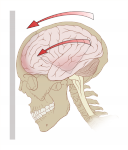

Garavito and undergraduates in the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making are working with a growing number of students, coaches, and administrators from high schools and colleges in New York (including Watkins Glen and Moravia high schools, Cornell University, and Ithaca College), Colorado, and Minnesota. Engagement with sports communities has provided the team with the opportunity to educate--and listen to-- the public about current research on concussions and how values or principles can affect perceptions and decisions about concussion risk. Garavito has found that coaches are very supportive of research projects that aim to help keep athletes safe and further knowledge about concussions. Many athletes have enthusiastically agreed to volunteer in Garavito’s studies. The student team also has been working with the Ithaca Youth Bureau and the experiences of coaches and educators at the center have been essential in the development of interactive activities to teach youth about the brain and concussions. The ultimate goal of the concussion intervention is to strengthen healthy values and educate people about risks, and the importance of reporting symptoms of concussions.

Garavito and undergraduates in the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making are working with a growing number of students, coaches, and administrators from high schools and colleges in New York (including Watkins Glen and Moravia high schools, Cornell University, and Ithaca College), Colorado, and Minnesota. Engagement with sports communities has provided the team with the opportunity to educate--and listen to-- the public about current research on concussions and how values or principles can affect perceptions and decisions about concussion risk. Garavito has found that coaches are very supportive of research projects that aim to help keep athletes safe and further knowledge about concussions. Many athletes have enthusiastically agreed to volunteer in Garavito’s studies. The student team also has been working with the Ithaca Youth Bureau and the experiences of coaches and educators at the center have been essential in the development of interactive activities to teach youth about the brain and concussions. The ultimate goal of the concussion intervention is to strengthen healthy values and educate people about risks, and the importance of reporting symptoms of concussions.