Dear Readers

FEATURES

Simple questionnaire predicts unprotected sex, binge drinking

Valerie Reyna and Evan Wilhelms developed a new questionnaire for predicting who is likely to engage in risky behaviors, including, unprotected sex and binge drinking. Their questionnaire significantly outperforms 14 other gold-standard measures frequently used in economics and psychology.

Valerie Reyna and Evan Wilhelms developed a new questionnaire for predicting who is likely to engage in risky behaviors, including, unprotected sex and binge drinking. Their questionnaire significantly outperforms 14 other gold-standard measures frequently used in economics and psychology.

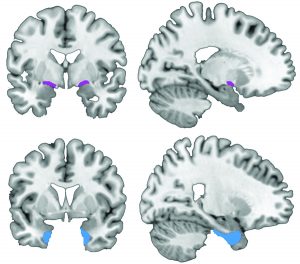

Study challenges model of Alzheimer's disease progression

The research of Professor Nathan Spreng and his collaborators sheds light on the basal forebrain region, where the degeneration of neural tissue caused by Alzheimer’s disease appears before cognitive and behavioral symptoms emerge.

The research of Professor Nathan Spreng and his collaborators sheds light on the basal forebrain region, where the degeneration of neural tissue caused by Alzheimer’s disease appears before cognitive and behavioral symptoms emerge.

Social media boosts remembrance of things past

A new study – the first to look at social media’s effect on memory – suggests posting personal experiences on social media makes those events much easier to recall.

A new study – the first to look at social media’s effect on memory – suggests posting personal experiences on social media makes those events much easier to recall.

Experts Address Elder Financial Abuse as Global Problem

Financial exploitation of older people by those who should be protecting them results in devastating health, emotional and psychological consequences. International elder abuse experts met at Weill Cornell Medicine to map out a strategy for conducting research on this problem.

Financial exploitation of older people by those who should be protecting them results in devastating health, emotional and psychological consequences. International elder abuse experts met at Weill Cornell Medicine to map out a strategy for conducting research on this problem.

For kids, poverty means psychological deficits as adults

Childhood poverty can cause significant psychological deficits in adulthood, according to a sweeping new study by Professor Gary Evans. The research, conducted by tracking participants over a 15-year period, is the first to show this damage occurs over time and in a broad range of ways.

Childhood poverty can cause significant psychological deficits in adulthood, according to a sweeping new study by Professor Gary Evans. The research, conducted by tracking participants over a 15-year period, is the first to show this damage occurs over time and in a broad range of ways.

STUDENTS IN THE NEWS

Miss New York Camille Sims fights for social justice

Camille Sims '15 says fate brought her to Cornell and the Department of Human Development. And now it has propelled her to reign as Miss New York and to finish second runner-up in September's Miss America competition.

Camille Sims '15 says fate brought her to Cornell and the Department of Human Development. And now it has propelled her to reign as Miss New York and to finish second runner-up in September's Miss America competition.

Summer Scholar Spotlight: Brian LaGrant ‘17

Brian LaGrant ’17, a human development major from New Hartford, N.Y., discusses his research on factors surrounding imitation among children and adults.

Brian LaGrant ’17, a human development major from New Hartford, N.Y., discusses his research on factors surrounding imitation among children and adults.

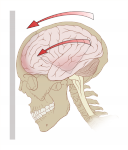

Risky decisions and concussions

David Garavito, graduate student in the Law, Psychology, and Human Development Program, under the supervision of Dr. Valerie Reyna, is working with communities in New York and around the country with support from an Engaged Cornell grant for student research. He is working with coaches and student athletes to study the effects of concussions on decision making about risks.

David Garavito, graduate student in the Law, Psychology, and Human Development Program, under the supervision of Dr. Valerie Reyna, is working with communities in New York and around the country with support from an Engaged Cornell grant for student research. He is working with coaches and student athletes to study the effects of concussions on decision making about risks.

ARTICLES ON THE WEB

Alzheimer’s early tell: The language of authors who suffered from dementia has a story for the rest of us

Adrienne Day writes about how Barbara Lust, professor in Human Development, and other researchers are studying changes in language patterns in early Alzheimer’s disease.

Adrienne Day writes about how Barbara Lust, professor in Human Development, and other researchers are studying changes in language patterns in early Alzheimer’s disease.

Garavito and undergraduates in the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making are working with a growing number of students, coaches, and administrators from high schools and colleges in New York (including Watkins Glen and Moravia high schools, Cornell University, and Ithaca College), Colorado, and Minnesota. Engagement with sports communities has provided the team with the opportunity to educate--and listen to-- the public about current research on concussions and how values or principles can affect perceptions and decisions about concussion risk. Garavito has found that coaches are very supportive of research projects that aim to help keep athletes safe and further knowledge about concussions. Many athletes have enthusiastically agreed to volunteer in Garavito’s studies. The student team also has been working with the Ithaca Youth Bureau and the experiences of coaches and educators at the center have been essential in the development of interactive activities to teach youth about the brain and concussions. The ultimate goal of the concussion intervention is to strengthen healthy values and educate people about risks, and the importance of reporting symptoms of concussions.

Garavito and undergraduates in the Laboratory for Rational Decision Making are working with a growing number of students, coaches, and administrators from high schools and colleges in New York (including Watkins Glen and Moravia high schools, Cornell University, and Ithaca College), Colorado, and Minnesota. Engagement with sports communities has provided the team with the opportunity to educate--and listen to-- the public about current research on concussions and how values or principles can affect perceptions and decisions about concussion risk. Garavito has found that coaches are very supportive of research projects that aim to help keep athletes safe and further knowledge about concussions. Many athletes have enthusiastically agreed to volunteer in Garavito’s studies. The student team also has been working with the Ithaca Youth Bureau and the experiences of coaches and educators at the center have been essential in the development of interactive activities to teach youth about the brain and concussions. The ultimate goal of the concussion intervention is to strengthen healthy values and educate people about risks, and the importance of reporting symptoms of concussions.