Reprinted from The Cornell Chronicle, September 14, 2017.

by Stephen D'Angelo

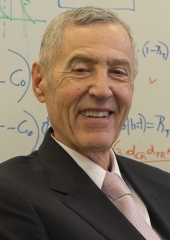

Stephen Ceci, the Helen L. Carr Professor of Developmental Psychology in the Department of Human Development, will receive the American Psychological Associations’ G. Stanley Hall award for distinguished contributions to developmental science at APA’s August 2018 meeting in San Francisco.

The highest honor in the field of developmental psychology, the award is given to an individual or research team who has made distinguished contributions to developmental psychology in research, student training and other scholarly endeavors.

“Steve has made seminal contributions to the basic scientific research of the developing mind in young children and to the critical translation of research findings to real-life settings,” said Qi Wang, professor of human development and department chair. “His work best exemplifies the integrative approaches that we take in the use of scientific theories and methods to vigorously study real-world problems in diverse populations.”

The award is based on the scientific merit of the individual’s work, the importance of this work for opening up new empirical or theoretical areas of developmental psychology, and the importance of the individual’s work in linking developmental psychology with issues confronting society or with other disciplines.

Ceci has written approximately 450 articles, books, commentaries, reviews and chapters. He has served on the advisory board of the National Science Foundation for seven years and was a member of the National Academy of Sciences’ Board of Behavioral and Sensory Sciences. He is past president of the Society for General Psychology, serves on 11 editorial boards, including Scientific American Mind, and is senior adviser to several journals.

Ceci’s honors include the American Academy of Forensic Psychology’s Lifetime Distinguished Contribution Award (2000), the American Psychological Association’s Division of Developmental Psychology’s Lifetime Award for Science and Society (2002), the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award for the Application of Psychology (2003), the Association for Psychological Science’s James McKeen Cattell Award (2005), the Society for Research in Child Development’s lifetime distinguished contribution award (2013) and the American Psychological Association’s E.L. Thorndike Award for lifetime contribution to empirical and theoretical psychology (2015).

Stephen D’Angelo is assistant director of communications at the College of Human Ecology.

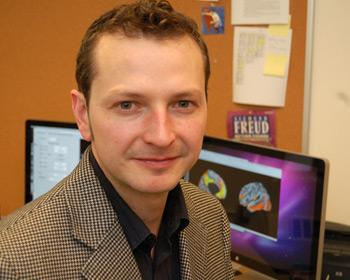

From an outside perspective, understanding a spoken language versus a signed language seems like it might involve entirely different brain processes. One process involves your ears and the other your eyes, and scientists have long known that different parts of the brain process these different sensory inputs.

From an outside perspective, understanding a spoken language versus a signed language seems like it might involve entirely different brain processes. One process involves your ears and the other your eyes, and scientists have long known that different parts of the brain process these different sensory inputs.

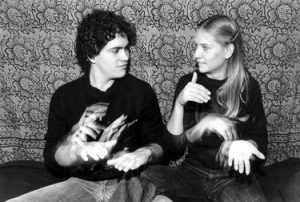

Happiness isn't the only emotion that can help you stay healthy as you age. How excited, amused, proud, strong and cheerful you feel on a regular basis matters, too. In a new study, people who experienced the widest range of positive emotions had the lowest levels of inflammation throughout their bodies. Lower inflammation may translate to a reduced risk of diseases like diabetes and heart disease.

Happiness isn't the only emotion that can help you stay healthy as you age. How excited, amused, proud, strong and cheerful you feel on a regular basis matters, too. In a new study, people who experienced the widest range of positive emotions had the lowest levels of inflammation throughout their bodies. Lower inflammation may translate to a reduced risk of diseases like diabetes and heart disease.